Peter Checkland Soft Systems Methodology Ebookers

Soft Systems Methodology was created by Peter Checkland for the main purpose of dealing with these large issues. During his career, he had been working with many hard systems methodologies. He saw how the current systems were inadequate for the purpose of dealing with high levels of complex problems, which had a large social component. Thirty years ago Peter Checkland set out to test whether the Systems Engineering (SE) approach, successful in technical problems, could be used by managers to cope with the unfolding complexities of everyday life. His findings were revealed in Systems Thinking, Systems Practice.

Introduction to SSM

Checkland distinguishes between the hard, engineering school of thought and soft systems thinking. The development of systems concepts and system thinking methods to solve ill-structured, “soft” problems is Checkland’s (1979) contribution to the field of systems theory. Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) provides a method for participatory design centered on human-centered information systems. It also provides an excellent approach to surfacing multiple perspectives in decision-making, complex problem-analysis, and socially-situated research. The analysis tools suggested by the method — which is really a family of methods, rather than a single method in the sense of modeling techniques — permit change-analysts, consultants and researchers to exercise reflexivity and to explore alternatives. In his valedictory lecture at Lancaster University, Peter Checkland listed four “big thoughts” that underlie soft systems thinking (Checkland, 2000):

1. Treat linked activities as a purposeful system.

2. Declare worldviews which make purposeful models meaningful (there will be many!).

3. Enact SSM as a learning system, finding accommodations enabling action to be taken.

4. Use models of activity systems as a base for work on information systems.

Treat linked activities as a purposeful system.

SSM is based upon a single concept: that we model systems of purposeful human activity (what people do), rather than width='980' cellspacing='0' cellpadding='0'>Customer: Who is the system operated for?

Who is the victim or beneficiary of this transformation-system?Actor(s): Who will perform the activities involved in the transformation process?

The actors represent a set of people who are acting in concert to achieve a specific purpose.

Actors also define the system boundary – who is inside or outside the system, from this perspective.Transformation: What single process will convert the input into the output?

The transformation defines the system purpose. If you have multiple verbs, this normally indicates that you are confusing or conflating two or more purposeful system views.Weltanschhaung

aka Worldview: What is the view which makes the transformation worthwhile?

Understanding this element communicates the how, what, why (context) of this system model.Owner: Who has the power to say whether the system will be implemented or not? (Who has the authority to make changes happen?)Environment: What are the constraints (restrictions) which may prevent the system from operating? What needs to be known about the conditions that the system operates under?

Enact SSM as a learning system

The purpose of SSM is to produce structured models that help in our thinking about the real world. But it is important to understand that these do not represent the real world. SSM is a process of analyzing subsets of human activity, to understand this activity at a deep level and to suggest ways of acting that improve the current “problem-situation”. It is not a way of modeling systems of work as they exist, or of defining computer-system functions. Rather, it is a way of engaging in joint learning about a real-world problem situation with participants in that situation, to explore relevant perspectives on its purposes, processes, and what needs to change.

Figure 2. SSM as a learning system (Checkland, 1979)

Systems thinking attempts to understand problems systemically. Problems are ultimately subjective: we select things to include and things to exclude from our problem analysis (the “system boundary”). But real-world problems are wicked problems, consisting of interrelated sub-problems that cannot be disentangled — and therefore cannot be defined objectively (Rittel, 1972; Rittel & Webber, 1973). The best we can do is to define problems that are related to the various purposes that participants pursue, in performing their work. by solving one problem, we often make another problem worse, or complicate matters in some way. So systemic thinking attempts to understand the interrelatedness of problems and goals by separating them out. In understanding different sets of activities and the problems pertaining to those activities as conceptually-separated models, we understand also the complexity of the whole “system” of work and the interrelatedness of things – at least, to some extent.

Use models of activity systems as a base for work on information systems

In much of his later work, Checkland addresses the difficulty of converting a model that represents a system of human activity into a set of requirements for an IT-based information system by distinguishing between the supporting system (IT) and the supported system (human activity). The supported system represents the problem domain, the amalgam of purposeful systems of human activity that underpins the problem situation. The supporting system represents the solution domain, that combination of people, processes, and technology that provides a solution to problems identified by participants in the problem situation.

Fig 3. The supporting system of IT vs. the supported system of human activity

Footnote

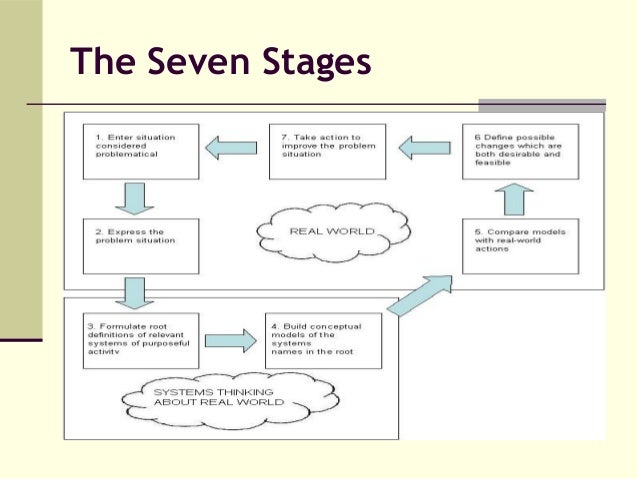

Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) was devised by Peter Checkland and elaborated in collaboration with Sue Holwell and Jim Scholes — among others — at Lancaster University in the UK. SSM provides a philosophy and a set of techniques (a method) for investigating a “real-world” problem situation. SSM is an approach to the investigation of the problems that may or may not require computer-based system support as part of its solution. In this sense, SSM could be described as an approach to early system requirements analysis, rather than a systems design approach. While the original, seven-step method of SSM (Checkland, 1979)has been replaced by more nuanced approaches to soft systems analysis (note the loss of the word “method”). Checkland now considers the approach more of a mindset, or way of thinking than a strict set of steps that should be followed (Checkland & Holwell, 1997). However, without the seven stages of thinking, it can be difficult to understand where to start. For this reason, many of the pages that follow employ the terminology and approach of the seven-stage method originally proposed.

Rhythm al ism dj quik rare. 'Time Iz Money' (feat. 'Words 2 My First Born' (feat. & )2001 -. 10.

This website attempts to explain some of the elements of SSM for educational purposes. It is not intended as a comprehensive source of information about SSM and may well subvert some of Checkland’s original intentions, in an attempt to make the subject accessible to students and other lifelong learners … .

References

Checkland, P. (1979) Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. Chichester UK. Latest edition includes a 30-year retrospective. ISBN: 0-471-98606-2.

Checkland, P. & Scholes, J. (1999) Soft Systems Methodology in Action. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. Chichester UK. ISBN: 0-471-98605-4.

Checkland, P., Holwell, S.E. (1997) Information, Systems and Information Systems.John Wiley and Sons Ltd. Chichester UK. ISBN: 0-471-95820-4.

Checkland, P. (2000) New maps of knowledge. Some animadversions (friendly) on: science (reductionist), social science (hermeneutic), research (unmanageable) and universities (unmanaged). Systems Research and Behavioural Science, 17(S1), pages S59-S75. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/75502924/abstract

Checkland, P., Poulter, J. (2006) Learning for Action: A Short Definitive Account of Soft Systems Methodology and its Use, for Practitioners, Teachers and Students. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. Chichester UK. ISBN: 0-470-02554-9.

Churchman, C.W. (1971) The Design of Inquiring Systems, Basic Concepts of Systems and Organizations, Basic Books, New York.

Rittel, H. W. J. (1972). Second Generation Design Methods. Design Methods Group 5th Anniversary Report: 5-10. DMG Occasional Paper 1. Reprinted in N. Cross (Ed.) 1984. Developments in Design Methodology, J. Wiley & Sons, Chichester: 317-327.: Reprinted in N. Cross (ed.), Developments in Design Methodology, J. Wiley & Sons, Chichester, 1984, pp. 317-327.

Rittel, H. W. J. and M. M. Webber (1973). “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences4, pp. 155-169.

Winter, M. C., D. H. Brown, et al. (1995). “A Role For Soft Systems Methodology in Information Systems Development.” European Journal of Information Systems4(3), pp. 130-142

von Bertanlaffy, L. (1968) General System theory: Foundations, Development, Applications, New York: George Braziller, revised edition 1976.

Soft systems theory

Acronym

SSM

Alternate name(s)

Soft systems methodology

Main dependent construct(s)/factor(s)

Problem solution

Main independent construct(s)/factor(s)

Context specific

Concise description of theory

Problems can be categorized as either ‘hard’ or ‘soft’, each with unique characteristics requiring distinctly different approaches to resolve. Hard problems are well defined where the “What” and the “How” can be determined early in the research or system design methodology. A definite solution exists and specific objectives may be defined. Hard problems constitute the essence of the systems engineering approach. In contrast, soft problems contain social and political elements that confound problem definition and resolution (also referred to as ‘wicked’ problems). The question of “How to improve national health care in the U.S.” represents a soft problem.

To address soft problems, Peter Checkland developed an iterative approach known as the Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) that consists of seven distinct stages:

- Define and understand the problem situation (i.e. nature of the process, key stakeholders, etc.).

- Express the problem situation through Rich Pictures.

- Select how to view the situation from various perspectives and produce root definitions.

- Build conceptual models of the system requirements to adequately address each of the root definitions.

- Compare the conceptual models (step 4) to the real world expression (step 2).

- Identify feasible and desirable changes to improve the situation.

- Develop recommendations for taking action to improve the problem situation (implementing step 6).

The intention of SSM is to provide a framework for addressing ill-structured and poorly defined problem situations that contain significant social effects. The researcher/ developer must investigate solutions that possess aspects other than merely technical functionality.

Diagram/schematic of theory

Originating author(s)

Peter Checkland

Seminal articles

Checkland, P. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice, John Wiley & Sons, London, 1981.

Originating area

Computer Science

Level of analysis

Individual, group, network

IS articles that use the theory

Atkinson, C. J. 'The Soft Information Systems and Technologies Methodology (SISTeM): an actor network contingency approach to integrated development', European Journal of Information Systems (9:2), June 2000, pp. 104-123.

Bausch, K.C. 'Roots and branches: a brief, picaresque, personal history of systems theory', Systems Research and Behavioral Science (19:5), September/October 2002, pp. 417-428.

Doherty, N. F. and King, M. 'The Importance of Organisational Issues in Systems Development', Information Techology and People (11:2), February 1998, pp. 104-123.

Jagodzinski, P., Reid, F. J. M., Culverhouse, P., Parsons, R. and Phillips, I. 'A Study of Electronics Engineering Design Teams', Design Studies (21:4), July 2000, pp. 375-402.

Janson, M. and Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. 'Making sense of e-commerce as social action', Information Technology & People (14:4), 2005, pp. 311-343.

Kiountouzis, E, Papatheodorou, C. 'Distributed Artificial Intelligence and Soft Systems: A Comparison', The Journal of the Operational Research Society (41:5), May 1990, pp. 441-446.

Ledington, J. and Ledington, P. W. J. 'Decision-Variable Partitioning: an alternative modelling approach in Soft Systems Methodology', European Journal of Information Systems (8:1), March 1999, pp. 55-64.

Ledington, P. W. J. and Ledington, J. 'The problem of comparison in soft systems methodology', Systems Research and Behavioral Science (16:4), July/August 1999, p. 329-339.

Links from this theory to other theories

General systems theory, Work systems theory

External links

http://sern.ucalgary.ca/courses/seng/613/F97/grp4/ssmfinal.html#MAP, Report from Department of Computer Science, University of Calgary .

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soft_systems, Wikipedia entry.

Original Contributor(s)

J. Randel Kuhn, Jr.

Please feel free to make modifications to this site. In order to do so, you must register.

Return to Theories Used in IS Research